By Susan Jarrett

Queen Victoria ruled England and Ireland until her death in 1901- making the Victorian Era one of the longest in history. For the purpose of these pages, the Victorian Era will be broken into a series of periods- The Crinoline (1850-1869), First and Second Bustle (1870-1890), and Turn of the Century (1890-1900).

The end of the 19th century, also known as the Fin de Siecle and The Gilded Age, brought forth a time of great economic prosperity juxtaposed with an overwhelming sense of social uneasiness across America. Although the American Civil War in the 1860s was successful in ending slavery and solidifying the philosophy of “one indivisible union,” it also spurred the notion that social institutions should be carefully scrutinized and reformed if necessary.

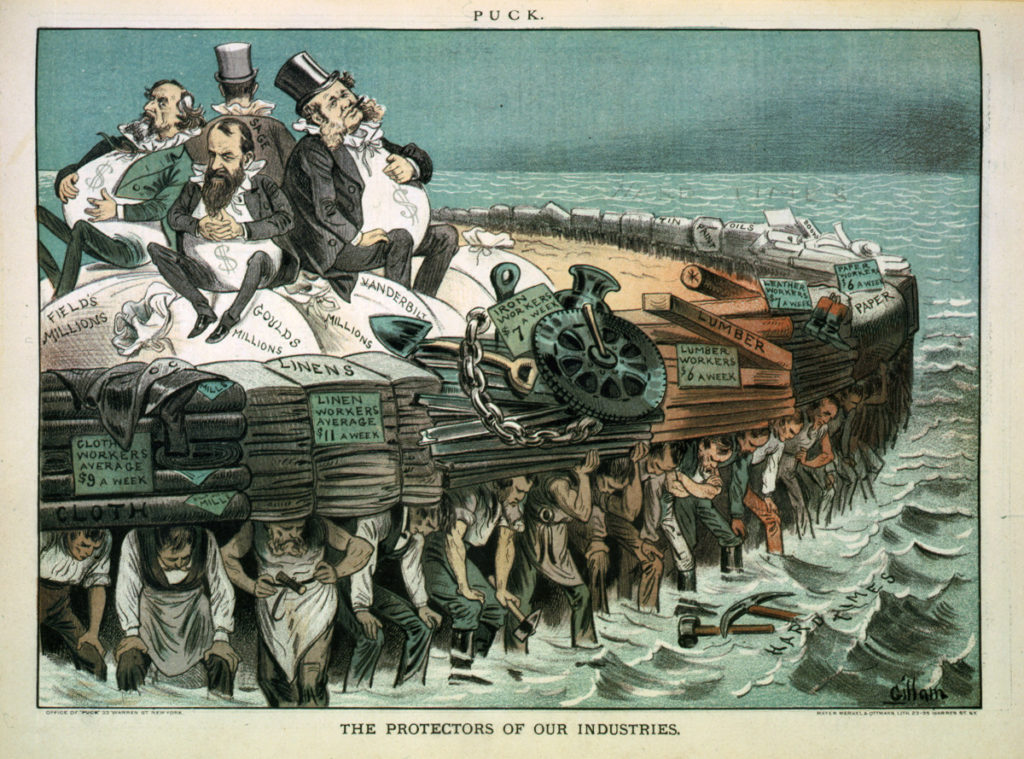

During the 1870s and 1880s, exponential economic growth created American millionaires like the Vanderbilts, the Carnegies, and the Rockefellers. However by the late 1890s, the economic boom of these decades quickly went bust and the nation fell into recession. From 1893-1897, many middle and working class men lost their jobs and their life savings. Families were turned out of their homes. By the beginning of the new century, the disparity gap between the wealthy and the poor had widened.

With the industrial boom of the 1870s, women began entering the workforce as factory laborers, mill workers, nurses, educators, and domestic servants. By 1890, over 5 million women were employed outside the home. The number of children working in textile mills rose 160% during this period and made up over one-third of the mills’ labor force.

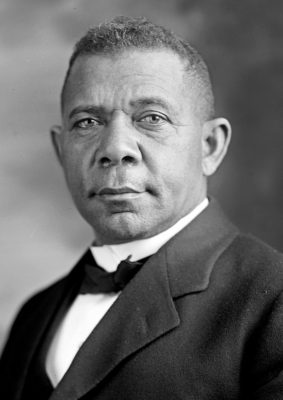

The loss of employment, the exploitation of child labor, unfair wages, poor working conditions, and the increasing tension between freed blacks and new immigrants led to outspoken cries for reform. During the 1890s, the Women’s Suffrage Movement began. The League for the Protection of the Family called for compulsory education for children in an effort to end child labor. Social workers published reports about the income, living conditions, and health of the nation’s poor. And political activists like Booker T. Washington argued equality for Americans of color.

The new industrialized lifestyle of the second half of the 19th century gave rise to the ready- made garment industry. This was a factory based system that mass produced articles of clothing in “standardized” sizing. However, standardization was only relative to each particular company or brand and thus wide variations in standard clothing measurements was common.

In 1862, the first department store opened in New York City offering ready- made clothing such as corsets, shoes, millinery, and outerwear. In addition, it offered a full range of home supplies, toys, and fine imported china.

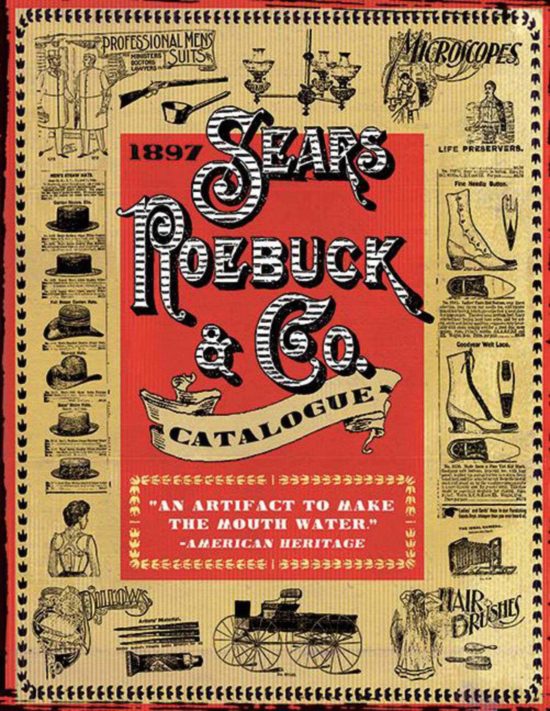

In 1872, Montgomery Ward sent its first catalog to farmers in rural parts of the nation- offering a variety of ready made items for purchase through mail-order. These mail order catalogs allowed customers in rural areas to “shop” the urban department stores via catalog. Customers filled out order forms, sent payments by money grams, and received their merchandise through the US Postal service. It was not long before the mail order industry flourished. In 1893 Sears, Roebuck, and Co. published their first mail order catalog.

E. Butterick and Co. (now known as simply Butterick) was the first to offer commercially produced patterns for the home seamstress. These were sold in shops and via mail order. By the Fin de Siecle, Butterick and Co. was the largest publisher of garment making patterns and print material in the United States.

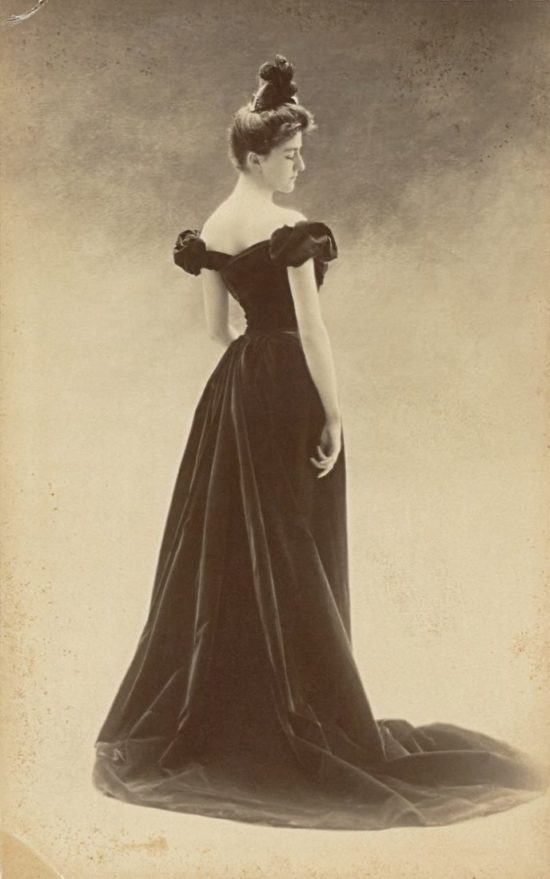

In 1890, Charles Dana Gibson revolutionized the American fashion world with his illustrations of a fictional female heroine lovingly referred to as The Gibson Girl. The Gibson Girl embodied the new feminine ideal. The American lady of the fin de siecle was stately, beautiful, and alluring. She was clever, creative, curious, athletic, and confident but lived within the parameters of the “feminine world” (unlike the 1890s era Suffragettes who wanted the same rights as men and were therefore deemed quite radical).

The rise of the “new woman” in America coincided with the decline of Queen Victoria’s Anglo-cultural influence. With failing health and widespread changes in societal values, by the turn of the century, Victorian principles were falling out of favor. Queen Victoria’s death in 1901 ended the reign of one of the United Kingdom’s longest ruling monarch. (In September 2015, Queen Elizabeth II surpassed Queen Victoria as Britain’s longest ruling monarch).

Women’s Clothing:

As more women entered the workforce, their wardrobes had to be adapted to the changing roles outside the home. Gone were the elaborate gowns with sweeping trains and gathered over-skirts. The former bustle of the 1870s and 1880s morphed into a nonintrusive skirt pad and the overall silhouette simplified. Interchangeable bodices and skirts became popular.

“The Scott” skirt improver. c. 1890s. FIDM.

The overall silhouette of this period was what we call “hour-glass“- wide at the shoulder, narrow at the waist, and wide again at the hips. This silhouette was achieved by wearing a tightly laced, heavily boned, mass produced corset that was preshaped into the hour-glass form. (This tight lacing sparked a reform movement by medical professionals and others concerned with the health effects of tightly fitted corsets). Some corsets ended just below the bust and were worn with a bust bodice to support the bosom. False bosoms or bust improvers were also worn to help create the illusion of a fuller torso.

Drawers, chemises, combinations, and petticoats continued to be worn and were often trimmed with intricate machine made tucks and lace details.

Late 19th century Reformist propaganda illustrations were used to promote the “ill effects” of the tightly fitted corsets. There is currently no scientific evidence that corsets worn during this period created permanent body damage. However, tight laced corsetry continues to be debated today.

Bodices were highly tailored and were made with supportive interior under- bodices. In the 1890s, extremely wide, leg-o-mutton sleeves (a revision of the Gigot and Demi-Gigot sleeves from the Romantic Era) were fashionable. Leg-o-Mutton sleeves puffed up and out at the shoulder and narrowed at the wrist- much resembling a leg of a lamb. Yokes, ruffles, and a variety of trims accented the breadth of the shoulders. Bodices typically ended at the natural waistline or had small basque waists. Some were tightly fitted and others were loosely gathered. Necklines varied from high to open and might include some type of lace or ruffle.

Skirts fit smoothly over the hips and flared out into a bell shape at the hem. The weight of the skirt shifted toward the back. Hemlines ended just a few inches above the floor or at the ankle.

Gowns for evening followed the silhouette of day wear. Evening bodices had square, rounded, or v-shaped necklines and sleeves typically ended above the elbow. Toward the end of the decade, sleeves with small puffs just at the shoulder line were popular. Skirts were floor length and were the only dresses to still have a train.

Hats were worn outdoors and were often elaborately decorated. Taxidermied birds, feathers, and silk flowers were popular millinery trims. Plain straw boaters and other hats with brims were popular. While bonnets were still worn during this period, the hat was all the rage.

Children’s Clothing:

While there is documentation to suggest that premade children’s attire existed as early as 17th century Europe, it was not until the 19th century industrial age (or the age of mass production) that ready made children’s garments were available to all social classes. Before the 1860s, ready made children’s clothing was only purchased by the upper class. Tailors and “little dressmakers” visited the home of the wealthy, taking measurements and fitting garments to each child. However, by the end of the 19th century, fashion called for loosely fitted dresses and less tailored suits- allowing for a “one size fits all” industry.

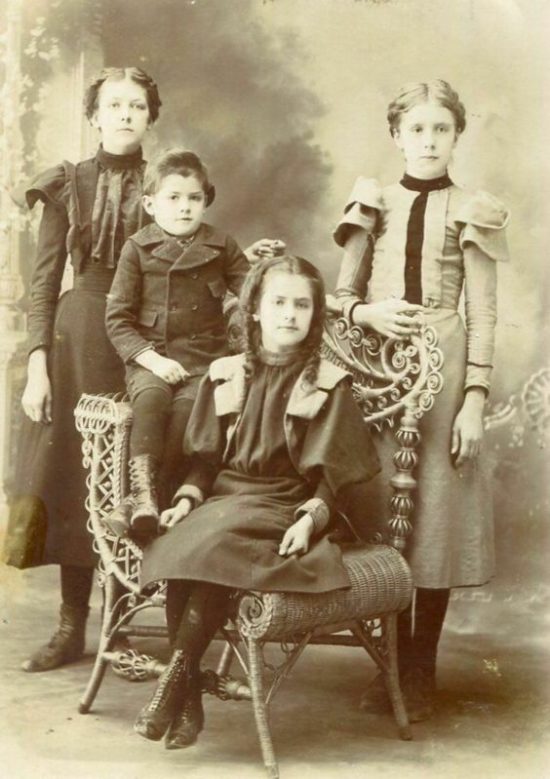

By 1890, the age of breeching for boys (the age when boy’s moved from dresses to knickers) dropped from five years to three years. This period saw a great military influence on boy’s clothing. Sailor suits, middies, and the reefer coat (a type of coat with a wide sailor collar and nautical braid) was popular for both boy’s and girls alike.

The brownie suit, now known as overalls, became popular for play and leisure activities. Knit-wear became popular for boy’s outer garments and included sweaters with high necks (now called the turtle-necks), pull- over sweaters, and button up sweaters (now known as cardigans).

Prior to the age of three, both boys and girls wore high waisted dresses- often trimmed with lace and ribbons. After the age of four, girl’s dresses followed the silhouette of the period (with large leg-o-mutton sleeves early in the decade but slowly deflating by the end of the decade). Waistlines typically ended at the natural waistline or just below. Nautical themes were extremely popular for girl’s dresses and included the sailor dress, dresses with sailor collars, and dresses trimmed with braid. For Sundays and other semi formal occasions, crisp white dresses were fashion dictatum.

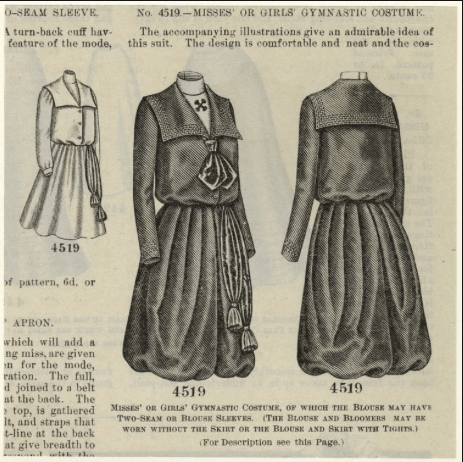

Girls also wore Turkish trousers (still called rationals in England)- or wide legged trousers gathered into a cuff at the knee. These trousers were worn for activities like cycling, gymnastics, tennis, and leisure activities.

CalicoBall is a grassroots effort to document, preserve, and present rural America’s diverse historical traditions. CalicoBall is an educational extension of Maggie May Clothing. ©2020 Maggie May Clothing.