by Susan Jarrett

The Victorian Era began in England in 1837 when William IV died without an heir to the throne- thus leaving his 18-year-old niece, Victoria, to become Queen. However, scholars do not begin to document the marked societal and cultural changes brought about by Queen Victoria’s England until about 1850.

Queen Victoria ruled England and Ireland until her death in 1901- making the Victorian Era one of the longest in history. For the purpose of these pages, the Victorian Era will be broken into a series of periods- The Crinoline (1850-1869), First and Second Bustle (1870-1890), and Turn of the Century (1890-1900).

The Victorian Era itself was a time of great change and progress- with its efforts to reform complex social institutions and its experimentations with mechanical and scientific ingenuities. The Victorian Era was highly moral. Motherhood was cherished and virtue was idolized. There was no greater icon of these ideals than the Queen herself, or the virtuous life of her husband Prince Albert. However, while this strict code of behavior greatly increased the civility and the gentility of life, it also encouraged an austere climate of conformity.

In 1851, Victoria’s husband Prince Albert, organized the first world’s fair. The Great Exhibition as it was called was the first public exhibition to display technological advancements and manufactured goods from around the globe. The Great Exhibition opened the door for an interchange of both cultural and artistic ideas from all over the world. An example of 19th century textile advancements include English chemist William Perkin’s discovery of a way to mass produce color, revolutionizing the fabric dyeing process. In 1858, he invented a new color synthetic known as mauve (a pale purple aniline dye) which the Queen wore to both her daughter’s wedding.

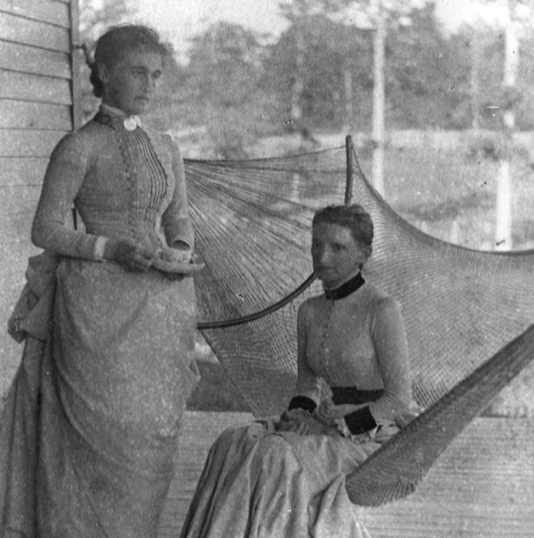

Another important innovation to impact this period is that of photography. In 1836, Louis Daguerre introduced a way to capture images by exposing copper and silver to a series of chemicals and salts. The type of photography is referred to as a daguerreotype. By 1850, a variety of photographic methods were available and the average citizen could now carry a true likeness of their loved ones.

The House of Worth and the rise of Couture:

France had not led the fashion world since the Regency period, but a designer by the name Charles Worth would change that. Worth, an Englishman who did not speak a word of French, began his career working in the fabric houses of Paris. Designing couture gowns in his spare time, he soon gained recognition in the fashion industry when he displayed some of his gowns in The Great Exhibition in London in 1851 and the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1855. In 1858, Worth opened his own house of fashion in Paris.

His gowns gained notice from the very influential fashionistas Empress Eugenie (wife of French Emperor Napoleon III) and Princess Metternich of Austria who became devoted patronesses. With their support, the success of The House of Worth was sealed.

But perhaps the most unique quality of Worth’s designs was that they were all interchangeable. Bodices, skirts, and sleeves were all drafted to fit any number of his designs and could be mixed and matched to create couture gowns custom to a client’s personal taste.

The Great Conflict:

In 1861, the worst conflict on American soil began as a civil war ripped across the nation. Just four years later, over 620,000 people would have lost their lives. With a nation at war, American industry and technology to support the effort was utmost priority. One of the technologies to revolutionize the war effort was the sewing machine.

Originally imported to America in the 1840s, American inventor Isaac Merritt Singer improved up on the efficiency of the original machine and in 1851 patented the first Singer Sewing Machine Company lock-stitch sewing machine. The Singer would revolutionize the garment making process by increasing the speed and efficiency with which garments could be made. By 1857, his sewing machine was available all over the United States. But it was the onset of the American Civil War that spurred it into regular use.

Garment making factories began popping up across the nation. The efficiently of a sewing machine reduced the amount of time it took to make a garment. Northern factories, fully equipped with sewing machines, worked day and night to keep their soldiers dressed. By the end of the war, they had made over 2 million uniforms.

In the American South, blockading and inflation abruptly halted major industrial and technological advancements. Both the shortage of goods coupled with increased pricing effected Southern fashion trends and led to the idea that Southern culture was antiquated and “old fashioned.” Unlike the mass production found in Northern factories, Southern civilians worked by candle light in their homes hand stitching uniforms for soldiers. On the home front, women were left to rely on their own ingenuity to repair, rework, or patch old and outdated garments.

Women’s Clothing:

This period derives its name from the invention of a women’s undergarment called the crinoline (later called the cage crinoline or hooped underskirt). The term crinoline refers to a stiffened skirt- typically some type of petticoat. By the 1850s, increasing skirt widths called for the reintroduction of the whalebone (or metal after 1857) hooped petticoat. (Whalebone hoops were worn during the early 18th century). By wearing the hooped petticoat, the wearer freed herself from the weightiness and cumbersome nature of multiple petticoats.

In the mid 1850s, the cage crinoline (or a petticoat made by sewing whalebone or steel bands to a series of tapes) allowed for even an even lighter undergarment. A single petticoat was worn over the top of the cage crinoline. Wool or flannel petticoats were worn in the winter for warmth.

During the Crinoline period, the corset (formerly referred to as stays) was a measure of decency. Corsets during this period were not tightly laced and were lightly boned with whalebone reinforcements. With the introduction of the cage crinoline, corsets were shortened and allowed for freedom of movement at the hips.

Bodices of this period ended slightly above the natural waistline. In the 1850s, feminine versions of men’s shirts, vests, and waistcoats were common separates. Thanks to the introduction of the sewing machine, time involved in making clothing was now drastically reduced and elaborate self- made trim work became popular. Lavish trimmings such as embroidery, ribbon, braid work, and ruching was used. Sleeves began to widen at the wrist and forearm. Undersleeves remained popular.

Early in the period, to emphasize the voluminous nature of the skirt, multiple outer flounces and overskirts became popular. By 1860, the ever-sought-after bell shaped skirt had disappeared and a preference for an oval shaped skirt became popular. In Europe, as early as 1861, the weight of the skirt had shifted backward and the appearance of a “flat-fronted” skirt emerged. Finer gowns often had an interchangeable day bodice and evening bodice worn with the same skirt.

Queen Victoria’s love for all things Scottish led to a craze for plaids. Plaid skirts, gowns, bows, neckties, and even sashes appeared in fashion all over Europe and The United States.

Throughout the entire Victorian period, the bonnet ruled the day as head wear. In the 1860s, younger ladies and ladies of fashion included a variety of hats into their wardrobe. Other head coverings worn in this period included lace or muslin day caps, ribbons, and jeweled hair ornaments.

Children’s Clothing:

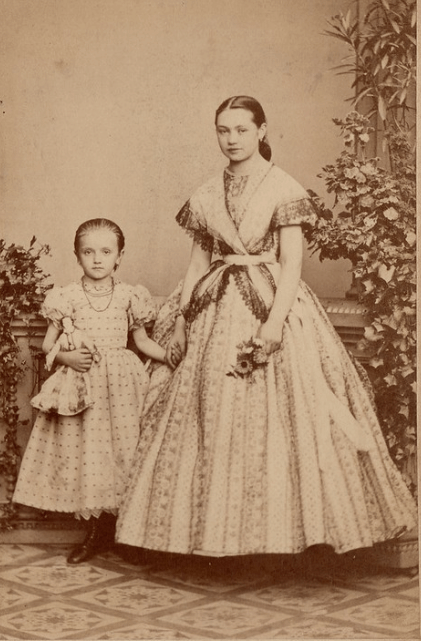

From toddler hood to the age of four, both girls and boys were dressed in gowns ending just below the knee accompanied by a set of pantalettes. After age four, little girls wore shorter versions of women’s fashions. As girls grew older, the skirt lengthened. By the age of 16, girl’s hemlines were approximately two inches above the ankle.

Hoops were worn by girls past the age four or five and pantalettes continued to be worn by all ages. Pantalette length ended anywhere from mid-calf to the ankle and it was not considered indecent for little girls and young ladies to allow the hems to peak out beneath their skirts.

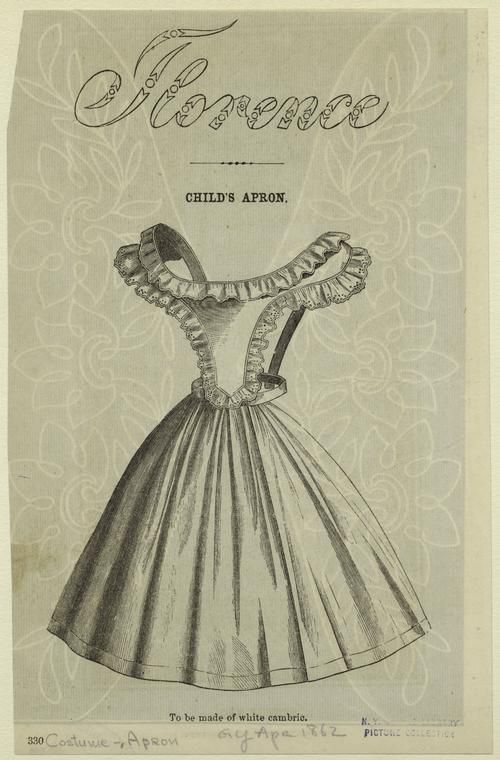

Pinafores were worn over dresses during the day to keep children’s clothing clean.

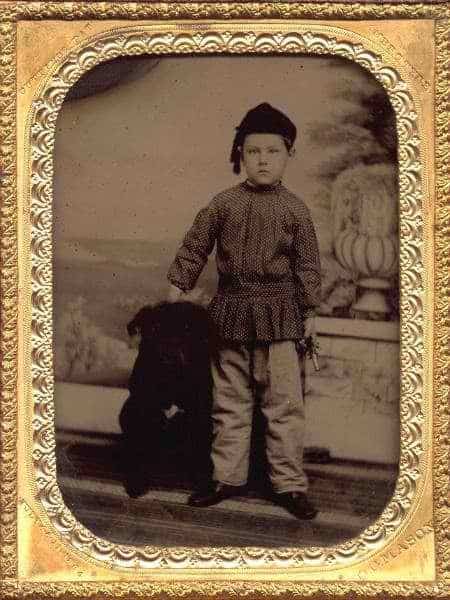

Little boys past the age four wore trousers and coats similar to that of their adult counterparts. The Eton suits and tunic suits of earlier decade were still in fashion. Knickerbockers and the Knickerbockers suit became popular attire for young boys during this period.

Overalls and smocks had been in use in rural areas since the 1830s and were worn as outer clothing during heavy labor. Young boys who helped their family work in the fields quite often had a one of these two garments to wear over their trousers and shirts.

CalicoBall is a grassroots effort to document, preserve, and present rural Americas diverse historical traditions. CalicoBall is an educational extension of Maggie May Clothing. ©2020 Maggie May Clothing